Gut bacteria

In Ancient Greece, Hippocrates believed that all diseases start in the gut. Thousands of years later and it looks like he had a point. More and more evidence is emerging that points to the pivotal role of the gut in health and disease and at gut bacteria (the microbiome) in particular.

We each have trillions of bacteria living in our gut, taking up residence from the moment we are born (some research suggests they might even start colonising before birth) and changing throughout our life span, influenced by everything from diet to medication, stress and trauma and even lifestyle choices.1 So far, research has shown that these bacteria can have a great effect on maintaining the mucosal barrier in the gut (to stop bad guys getting out into the bloodstream and wreaking havoc)1, extracting nutrients and energy from food (it has even been suggested that obese individuals have bacteria that is especially adept at this)2, and in immunity – 70% of your immune system is actually in your gut!1 Evidence also shows a gut-brain connection, and there is a link between disturbance of gut bacteria and mood, with one study alleging 60% of anxiety and depression patients had bacterial imbalance.3 Much more research is needed but the implications for our health are really exciting.

An aspect of gut bacteria that I see most commonly in clinic is something called ‘dysbiosis.’ This is when beneficial bacteria and less beneficial bacteria become imbalanced.4 Symptoms are incredibly varied, ranging from IBS type symptoms, tummy aches, flatulence, abdominal discomfort, irregular bowel habits, to symptoms that you might not think could be connected to the gut – for example fatigue, aches and pains, anxiety, depression. Dysbiosis is something I often look to address first, before moving on to look at a client’s other imbalances, because if the gut isn’t working optimally it can be very difficult to adequately process and absorb all the nutrients needed to keep the rest of the body functioning optimally.

The great news is that we can use diet to keep our gut bacteria happy, and here are some ideas you can try:

- Gut bacteria love veggies, and they love variety! So try to eat a rainbow everyday – orange, red, purple, white, green veggies. Not only will you reap the benefits of a variety of antioxidants, polyphenols and phytonutrients but you’ll also be getting a healthy dose of fibre. Fibre helps your bacteria thrive.5

- Fermented foods: natural yoghurt, kefir, kombucha, sauerkraut, miso, kimchi, apple cider vinegar, fermented pickles, tempeh, unpasteurized cheese. These contain bacteria that can help to colonize your gut with the good guys. (Top tip – always buy fermented foods that have to live in your fridge. If it’s a store-cupboard item, it probably doesn’t have enough bacteria. For example, most supermarket pickles will not be fermented – you’d have better luck at a health food shop. You could also try making them yourself.)6

- Reducing processed foods and alcohol. These are bad news for the gut, suppressing good bacteria and feeding the bad guys.7

- Don’t take antibiotics unless your GP tells you they’re necessary. Antibiotics flush out all bacteria – good and bad. Interestingly, a recent study suggests that the microbiome recovers more quickly than previously thought from a course of antibiotics, but several key beneficial strains of bacteria take slightly longer.8 If you have had to take antibiotics, try to gradually reintroduce bacteria.

- Lifestyle – stress, lack of sleep and lack of exercise have all been linked to a reduction in the diversity of gut bacteria. Try to relax, get enough shut-eye and exercise regularly.9

It’s important to take it slow when introducing more fibre or fermented foods into your diet. Adding too much too soon can result in more digestive symptoms – particularly abdominal discomfort and wind. It is also possible to take probiotic supplements, which can be really helpful for certain individuals. I would always suggest trying a ‘food-first’ approach – get as much as you can from your diet before turning to supplements.

References

- Thursby, E. and Juge, N. (2017). Introduction to the human gut microbiota. Biochemical Journal, 474(11), pp.1823-1836.

- Castaner, O., Goday, A., Park, Y., Lee, S., Magkos, F., Shiow, S. and Schröder, H. (2018). The Gut Microbiome Profile in Obesity: A Systematic Review. International Journal of Endocrinology, 2018, pp.1-9.

- Liu, L. and Zhu, G. (2018). Gut–Brain Axis and Mood Disorder. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 9.

- Hooks, K. and O’Malley, M. (2017). Dysbiosis and Its Discontents. mBio, 8(5).

- Hiel, S., Bindels, L., Pachikian, B., Kalala, G., Broers, V., Zamariola, G., Chang, B., Kambashi, B., Rodriguez, J., Cani, P., Neyrinck, A., Thissen, J., Luminet, O., Bindelle, J. and Delzenne, N. (2019). Effects of a diet based on inulin-rich vegetables on gut health and nutritional behavior in healthy humans. The American Journal of Clinical Nutrition, 109(6), pp.1683-1695.

- Rezac, S., Kok, C., Heermann, M. and Hutkins, R. (2018). Fermented Foods as a Dietary Source of Live Organisms. Frontiers in Microbiology, 9.

- Zinöcker, M. and Lindseth, I. (2018). The Western Diet–Microbiome-Host Interaction and Its Role in Metabolic Disease. Nutrients, 10(3), p.365.

- Palleja, A., Mikkelsen, K., Forslund, S., Kashani, A., Allin, K., Nielsen, T., Hansen, T., Liang, S., Feng, Q., Zhang, C., Pyl, P., Coelho, L., Yang, H., Wang, J., Typas, A., Nielsen, M., Nielsen, H., Bork, P., Wang, J., Vilsbøll, T., Hansen, T., Knop, F., Arumugam, M. and Pedersen, O. (2018). Recovery of gut microbiota of healthy adults following antibiotic exposure. Nature Microbiology, 3(11), pp.1255-1265.

- Conlon, M. and Bird, A. (2014). The Impact of Diet and Lifestyle on Gut Microbiota and Human Health. Nutrients, 7(1), pp.17-44.

Poo Taboo

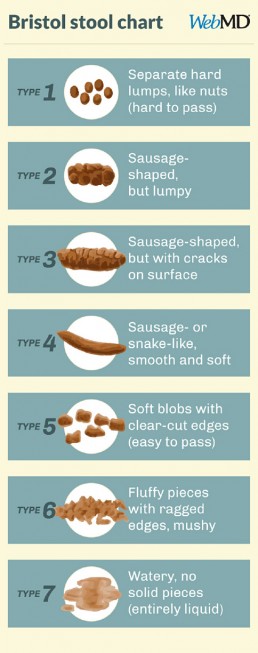

People don’t talk about poo. It’s considered ‘bad taste,’ or ‘immature.’ Yet it can be one of the most useful indicators about what is going on in the body – the shape, size, colour and consistency alone can give us lots of clues and a useful tool I use in clinic to get the conversation rolling is the Bristol Stool Chart. Yes, if you come and see me, you can expect me to bring out a laminated sheet displaying different drawings of poo!

Generally speaking, types 3 and 4 are the ‘optimum’ stools, and you’d want to be producing them between 1-3 times most days. They should be easy to pass and painless, and not associated with any immediate urgency – i.e. if you have to wait until you find a loo it wouldn’t be uncomfortable. I say ‘generally’ because we are all different and there might be cases when an individual’s bowel habits don’t conform to the ‘optimum’ but are still perfectly healthy for them.

It’s also quite normal for stools to vary depending on what you’ve been eating most recently or how your lifestyle has been. For instance, have you ever been on holiday and not pooped for several days? Believe it or not, change in routine can really disrupt your loo schedule! Stress, medication, alcohol, indulgent meals, the menstrual cycle and illness can all impact and alter bowel movements but if you’re regularly experiencing constipation or urgency and loose stools, it might be a good idea to talk to someone.

Let’s look at the stool chart in more detail.

Types 1 and 2 are likely to go hand in hand with less frequent trips to the loo, or even with constipation. It might be that you’re dehydrated and need a bit more water – the body will draw water back out from the colon in order to compensate for the dehydration, making stools firmer and harder to pass. It might be that your fibre intake is low – these stools might be expected if you’re following a diet low in carbohydrates. It can even be a sign that you’ve been inactive – exercise can help to get things moving. These stools will have spent longer in the colon than is ideal, allowing for the reabsorption of toxins that should have been eliminated, including excess hormones. This is one reason why addressing bowel movements is a key part of supporting detoxification.

Types 5, 6, and 7 are likely to be more frequent, possibly associated with an urgency to go. It is likely that the stool has spent less time in the colon, therefore leaving less opportunity for food and water to be absorbed which is why these stools are looser, possibly indicating diaorrhea. Since less water is being absorbed, it is important to drink plenty of fluids in order to replenish. These types might also be indicative of a low fibre diet, since the stools are not firm.

Other aspects of appearance such as colour and greasiness, along with smell, are also useful indicators of what else might be going in in the gut. An ‘ideal’ poo (again, we’re speaking generally here) might be a mid-dark brown, wouldn’t leave marks on the toilet bowl and wouldn’t have a strong odour.

If you’d like to find out more about what your bowel movements might mean, please do get in touch and we can discuss how to optimize your digestion. There are even functional tests that can be done where a sample of your stool is sent to a laboratory to find out all sorts of more detailed information such as the composition of the bacteria in the gut, the level of enzymes that help to digest protein, carbohydrate and fats, whether there is any inflammation in the gut and even whether there are any yeast, microbes or parasites present. I’m very happy to break to poo taboo and get talking!

REFERENCES

Blake, M., Raker, J. and Whelan, K. (2016). Validity and reliability of the Bristol Stool Form Scale in healthy adults and patients with diarrhoea-predominant irritable bowel syndrome. Alimentary Pharmacology & Therapeutics, 44(7), pp.693-703.

Chang, Y., El-Zaatari, M. and Kao, J. (2014). Does stress induce bowel dysfunction?. Expert Review of Gastroenterology & Hepatology, 8(6), pp.583-585.

WebMD. (2019). What Kind of Poop Do I Have?. [online] Available at: https://www.webmd.com/digestive-disorders/poop-chart-bristol-stool-scale [Accessed 6 Aug. 2019].

Blood Glucose - The key to sustained energy

Ever heard of ‘food coma’? Ever had that post-lunch energy slump? Ever been ravenous mid-morning even though you had a big brekky? Chances are your blood glucose isn’t balanced. It’s one of the most common things I see in clinic and is often the starting point for my nutrition plans because without balanced blood glucose, it’s very difficult to bring everything else in the body into balance as well.

What is ‘blood glucose’?

When you eat, food gets broken down as it travels through the digestive system. As a result of this, the sugars (glucose) from foods are released into the blood stream. When this happens, a hormone called insulin is released from the pancreas (a large gland that sits behind the stomach). Insulin’s job is to encourage the cells in the body to let glucose in, where it will be used for energy. As the amount of glucose entering the blood stream falls, so does the level of insulin.

If too much glucose is released into the bloodstream, more insulin is released from the pancreas. It then stores the excess glucose in the liver, which will release it when more glucose is needed by the body – for example during exercise or between meals. This is supposed to be a good thing, making sure that your body has sustained energy.

When does blood glucose become imbalanced?

Different foods will have different effects on blood glucose – particularly depending on the protein, fat and fibre contents. But in simplistic terms, foods high in refined carbohydrate and sugars will cause a quicker and sharper spike in blood glucose. This leads to a quicker release and higher volume of insulin which will then lead to a quicker and sharper fall in the level of glucose in the blood. We refer to this as the ‘blood glucose rollercoaster.’

What does this actually mean?

These peaks and lows in blood glucose levels will result in peaks and crashes in energy – in other words, that mid-afternoon energy slump or that post-dinner ‘food coma.’ They’ll also make you hungry shortly after eating, irritable, possibly dizzy, have difficulty focusing and that dreaded feeling of hanger.

If blood glucose becomes dysregulated long-term, the knock-on effects can be widespread because insulin can interact with various other hormonal systems in the body. It is implicated in the balance of sex hormones and therefore plays a role in conditions such as endometriosis and PCOS, as well as PMS. It can affect hormones that relate to mood and stress. It can be linked to systemic inflammation and sleep disorders.

How to balance blood glucose?

The good news is that it’s actually relatively easy to balance blood glucose through your diet. Including plenty of fibre, protein, healthy fats and complex carbohydrates whilst reducing your intake of processed and refined carbohydrate foods. If you’re interested in finding out more please do get in touch with me at laura@lmnutrition.co.uk

Plant based protein

I sometimes receive an eye-roll when I discuss the importance of protein – people tend to think it’s for body-builders, personal trainers and weight-loss. Let me set the record straight – we ALL need plenty of protein. Without it, our bodies simply cannot function properly.

Protein is made up of amino acids, which are like the building blocks of the body. They build muscles and are essential for growth and repair.1 They form enzymes which facilitate biochemical reactions – digestion, muscle contraction, energy production and blood clotting are all dependent on enzymes.2, 3 They help to form antibodies to fight infection.4 They transport nutrients around the body. They are essential to detoxification pathways.5 Every single cell in the body has a protein component.

Without sufficient protein, we increase our risk of catching coughs and colds, reduce our ability to detoxify, we can suffer mood symptoms including depression, struggle with sleep, have digestive issues and even struggle with fertility. Yes, protein is that important.

There are about 20 amino acids, 11 of which can be made endogenously (in the body) and 9 of which must be obtained through diet. These are the ‘essential amino acids’: histidine, isoleucine, leucine, lysine, methionine, phenylalanine, threonine, tryptophan, and valine.6

Meat, fish, eggs and dairy contain all of these, but most plant-based proteins do not. Therefore, if you’re following a vegetarian or especially a vegan diet, variety really is key! By eating a wide variety of plant-based food throughout the day, you’re more likely to obtain all 9 essential amino acids.

Some of the most commonly used plant proteins are quinoa (the only plant-based complete protein – it contains all amino acids), tofu, tempeh, pulses (lentils, beans and peas), nuts and seeds, oats, rice and green vegetables.

Here’s an example of how you could get a variety of plant protein across one day of eating:

- Breakfast: overnight oats with chia seeds, fresh berries and nut butter

- Lunch: quinoa salad with tofu, dark leafy green and coloured vegetables

- Snack: carrot sticks with hummus or edamame beans

- Dinner: mixed bean chilli with guacamole and green vegetables

Oats, chia seeds, nut butter, quinoa, tofu, dark leafy green vegetables, hummus, edamame, beans and more green vegetables – a protein powerhouse!

References:

- Wu, G. (2009). Amino acids: metabolism, functions, and nutrition. Amino Acids, 37(1), pp.1-17.

- Wu, G. (2010). Functional Amino Acids in Growth, Reproduction, and Health. Advances in Nutrition, 1(1), pp.31-37.

- Wang, W., Qiao, S. and Li, D. (2008). Amino acids and gut function. Amino Acids, 37(1), pp.105-110.

- Li, P., Yin, Y., Li, D., Woo Kim, S. and Wu, G. (2007). Amino acids and immune function. British Journal of Nutrition, 98(2), pp.237-252.

- Hodges, R. and Minich, D. (2015). Modulation of Metabolic Detoxification Pathways Using Foods and Food-Derived Components: A Scientific Review with Clinical Application. Journal of Nutrition and Metabolism, 2015, pp.1-23.

- Hou, Y., Yin, Y. and Wu, G. (2015). Dietary essentiality of “nutritionally non-essential amino acids” for animals and humans. Experimental Biology and Medicine, 240(8), pp.997-1007.

Supplements

The market for food supplements is booming. A 2018 report for the UK Food Standards Agency suggesting that by 2021 it will be a £1 billion market.1 The same report noted that many people were taking daily supplements with a ‘better safe than sorry’ attitude, hoping to support health and believing there to be no real danger in regularly taking supplements purchased from a high street health food chain.1

In my opinion there are three key points to make clear about supplements:

1. Supplements are not always safe

2. Supplements are often not as effective as food

3. High quality supplements can be a useful short-term strategy to optimize health

1. Supplements are not always safe

There are circumstances in which certain supplements can do more harm than good. For instance, many supplements interact with medication – either increasing or reducing its affects.2 Many supplements can cause toxicity at high doses – e.g. iron.3 There are also supplements that might be useful for short-term use, but potentially damaging for long-term use. There are supplements for which research on long-term use does not yet exist. A qualified Nutritional Therapist, Nutritionist or Dietician will be trained in understanding and researching which supplements might be useful and which are to be avoided for each individual client.

2. Supplements are often not as effective as food.

This is largely due to the fact that nutrients do not work in isolation. All processes in the body require a combination of nutrients, and many of these nutrients even require others in order to be absorbed into the blood stream. For instance, vitamins A, D, E and K are ‘fat-soluble’ – to absorb them, you need fat.4 Another example is that calcium needs vitamin D in order to get into bones and teeth where it is a vital nutrient.5 Simply popping a pill with one of these nutrients isn’t actually going to help the body – in many cases, supplements purchased from high street brands will simply pass straight through you! In contrast, many food sources of vitamins A, D, E and K already contain fats, and many sources of calcium already contain vitamin D. Higher quality supplement brands are more carefully formulated to include nutrients that enhance each other’s bioavailability – the ability to be absorbed and utilised by the body. A qualified professional can help source and recommend these if appropriate.

3. Supplements carefully selected and tailored to an individual’s needs can be a useful short-term strategy to optimise health

I do use supplements in clinic in short-term, ‘therapeutic’ doses. A carefully selected dose of certain nutrients can help the body to re-establish it’s optimal state – be that in terms of hormonal balance, digestive function or any other system function. The idea of this is to then add more foods into the diet that contains those nutrients, so that an individual can obtain everything required for healthy body function from diet alone. In some cases this might be impossible and a supplement might be required long-term, for instance in certain conditions or if someone is following a vegan diet, but this should always be monitored by a qualified Nutritionist or in some cases by a GP.

References

1. Food.gov.uk. (2018). Food Supplements Consumer Research: Final Report for Food Standards Agency. [online] Available at: https://www.food.gov.uk/sites/default/files/media/document/food-supplements-full-report-final-2505018.pdf [Accessed 30 Jul. 2019].

2. NCCIH. (2019). Know the Science: How Medications and Supplements Can Interact. [online] Available at: https://nccih.nih.gov/health/know-science/how-medications-supplements-interact?page=3 [Accessed 30 Jul. 2019].

3. Abbaspour, N., Hurrell, R., & Kelishadi, R. (2014). Review on iron and its importance for human health. Journal of research in medical sciences : the official journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, 19(2), 164–174.

4. British Nutrition Foundation. (2019). Vitamins – British Nutrition Foundation. [online] Available at: https://www.nutrition.org.uk/nutritionscience/nutrients-food-and-ingredients/vitamins.html [Accessed 30 Jul. 2019].

5. Wimalawansa, S., Razzaque, M. and Al-Daghri, N. (2018). Calcium and vitamin D in human health: Hype or real?. The Journal of Steroid Biochemistry and Molecular Biology, 180, pp.4-14.

Veganism

Increasing numbers of people are turning to veganism – a diet free from all animal-derived products. Ethical and environmental factors aside, what does this mean for health?

There aren’t many long-term studies on the effects of a vegan diet but what is clear is that a poorly planned vegan diet is likely to be lacking certain essential nutrients required by the body. It therefore takes careful consideration to ensure that you’re not missing out on anything that’s going to impact your overall health. The most common deficiencies in a vegan diet are protein (I’ve written a separate post about plant-based protein), vitamin B12, Omega 3, Iron and vitamin D.

Vitamin B12

This is a vitamin predominantly found in animals and therefore almost impossible for someone who is vegan to obtain through diet alone. It is essential for brain function and red blood cell production and deficiency can impact neurological health and has been linked to anaemia.1 Foods fortified with vitamin B12 are a viable option – for instance many plant-milks, but the quantity of B12 will vary. It may be advisable to consider a B12 supplement, but please only do so having spoken to a professional (see my post on why you should seek advice before starting a supplement program).

Omega 3

Research has shown that omega 3 fatty acids are important for heart health, reducing inflammation, healthy bones and joints, skin health, blood sugar balance and have even been linked to mental health (though further research is needed).2, 3, 4 There are 3 key types of omega 3 fatty acids, alpha-linolenic acid (ALA), docosahexaenoic acid (DHA) and eicosapentaenoic acid (EPA). ALA cannot be produced endogenously (in the body) so must be obtained from the diet – it then helps the body to produce EPA and DHA. Vegan sources of ALA include chia, hemp and flax seeds. It is also possible to get EPA and DHA through an algae-based supplement – a professional can advise you on this.

Iron

Iron vital for numerous metabolic processes, the health of your red blood cells, and delivering oxygen to every cell in the body.5 There are two forms of iron: heam iron (from animals) and non-haem iron (from plants). Non-haem iron is less ready absorbed and utilized by the body than haem iron, but absorption can be increased by including foods rich in vitamin c. The good news is that the plant world is so clever that many vegetables high in iron also contain vitamin C – like dark leafy green vegetables. You could also try serving your greens with a squeeze of lemon juice to boost the vitamin C. Lentils, kidney beans and pumpkin seeds have high levels of iron. It is never advisable to supplement with iron unless you have had your iron levels measured – this is because iron can become toxic in high volumes.

Vitamin D

Vitamin D has many roles in the body, including helping calcium be absorbed into the bones, facilitating gene expression6,

regulating blood pressure7 and supporting the immune system – with a possible role in autoimmune conditions too.8 In the UK, most of us are not getting sufficient vitamin D intake from sun exposure alone and must therefore look to our diets, but the main dietary sources are meat, fish and eggs. It is now widely recommended that we supplement vitamin D through the winter, but another easy way to get some more into a vegan diet is through fortified foods such as many widely available plant milks.

These are just the basics but if you are vegan, or are considering following a vegan diet, I strongly recommend either asking for help from a qualified professional (come see me!) or taking some time to research what you will need to include on a regular basis.

References:

1. Rizzo, G., Laganà, A., Rapisarda, A., La Ferrera, G., Buscema, M., Rossetti, P., Nigro, A., Muscia, V., Valenti, G., Sapia, F., Sarpietro, G., Zigarelli, M. and Vitale, S. (2016). Vitamin B12 among Vegetarians: Status, Assessment and Supplementation. Nutrients, 8(12), p.767.

2. Bozzatello, P., Brignolo, E., De Grandi, E. and Bellino, S. (2016). Supplementation with Omega-3 Fatty Acids in Psychiatric Disorders: A Review of Literature Data. Journal of Clinical Medicine, 5(8), p.67.

3. Swanson, D., Block, R. and Mousa, S. (2012). Omega-3 Fatty Acids EPA and DHA: Health Benefits Throughout Life. Advances in Nutrition, 3(1), pp.1-7.

4. Gammone, M., Riccioni, G., Parrinello, G. and D’Orazio, N. (2018). Omega-3 Polyunsaturated Fatty Acids: Benefits and Endpoints in Sport. Nutrients, 11(1), p.46.

5. Abbaspour, N., Hurrell, R., & Kelishadi, R. (2014). Review on iron and its importance for human health. Journal of research in medical sciences : the official journal of Isfahan University of Medical Sciences, 19(2), 164–174.

6. Heaney, R. (2008). Vitamin D in Health and Disease. Clinical Journal of the American Society of Nephrology, 3(5), pp.1535-1541.

7. Jeong, H., Park, K., Lee, M., Yang, D., Kim, S. and Lee, S. (2017). Vitamin D and Hypertension. Electrolytes & Blood Pressure, 15(1), p.1.

8. Aranow, C. (2011). Vitamin D and the Immune System. Journal of Investigative Medicine, 59(6), pp.881-886.